Sunday, July 31, 2005

Another post-call morning

I was called early in the morning (~4:30) for a few issues in the ICU, so after taking care of those, I decided I should go ahead and round and write my notes. Since I'm finished with my work early, I hope to grab a bite of breakfast and make it to church after checking my patients out to my cross cover.

As we ate dinner last night, Clay and I talked about a few of our patients, and the sad situations we've seen. I know my friend DoctorJ has addressed this in his blog, but it's weird how we learn to separate ourselves from suffering. It's not that we're callous or uncaring; rather I think it's more out of ncessity. For instance, I could enjoy my chicken picatta, mashed potatoes, and broccoli while we discussed a patient who'd been placed on "comfort care," which means all therapeutic medical intervention had been withdrawn, and the patient was simply being kept as comfortable as possible while she died. And this is one of many. There's the 20-something-year-old girl with a history of physical abuse, rape, and substance abuse who killed her brain with insulin. There's the 35-year-old man with metastatic pancreatic cancer I met late one night in the ICU as I was covering overnight. He has a wife and young children. And there's the 45-year-old East African man I recently admitted with aggressive stomach cancer...his family is praying for a miracle.

I'm reminded of my stroke patient early in July. After turning back and seeing her one last time after I'd written the orders to discontinue her feeding tube, I cried as I left the hospital. It can be wearing to be around so much suffering, and yet it's a blessing. I am paid to relieve pain and suffering, to be a healer, which is an amazing privilege. And I'll use all God has given me to do just that.

Saturday, July 30, 2005

Things I'll miss about this city...

Arranged in no particular order, I've compiled a list of things I've enjoyed about living in this city. Ever since finding out in March that I'm leaving in June 2006, I've felt a little more nostalgic. There's still a lot to take in during the next 11 months!

Things I'll Miss

- Great sunsets in a huge sky

- My church (especially the organ & Colin, who plays it. And we couldn't forget the wonderful keyboard work of Stephen and Alex. All three of these men are masters. If they were Japanese cartoon characters, Colin's special power would be improv; Stephen, phrasing; and Alex, rubato.)

- Driving on the major north-south artery through town.

- Great local barbecue

- The fantatic view of downtown from various places in the city.

- The symphony center--all cold metal, stone, and glass outside, but dark blue, rich woods, and warm lights inside. Dozens of great concerts within its walls. A fantastic choral loft which is a small compromise on acoustics, but a great deal on price and visuals!

- The mansions on A_____. One of my favorite is an 80-year old home which is stately but not pretentious.

- The irony of life in this city. The "pretense" within some neighborhoods, and the readiness to spot & criticize pretense by those without.

- Driving through downtown.

- Visiting a local exclusive girls' school as a first year medical student taking "Human Behavior." We were to observe the way the children interact. This is a place, however, where girls quickly line up in gym class when the whistle is blown, where everyone wears plaid skirts, where any ol' first grader can tell you the definition of libretto, and where they serve "grilled tilapia," not "fish" for lunch.

- Studying with friends at various Borders and of course the big Barnes & Noble, back when they let you sit at the tables for hours!

- The major airport. This airport is extremely well laid-out, making it easy to park to nearly any gate.

- Delivering babies at the county hospital.

- The crazy experiences in the ~200+ hours I've worked in the psychiatric E.R.

- Teaching anatomy lab to first-year medical students

- Spiced chai at the Black Forest Cafe (at Half Priced Books)

- The gargantuan Half Priced Books.

- Beautiful churches.

- The classical music radio station, especially Adventures in Good Music with Karl Haas, and Sunday afternoon listener requests.

- Running on the local running trail. This is where Adam both inspired me and pushed me to the point of nausea.

To be continued...

Friday, July 29, 2005

It's a sunny day, and I feel great!

One encouragement is that this morning, several little things look better with my ICU pancreatitis patient. He's certainly not out of the woods, but I hope this is the first step of many on the road to recovery.

Took the time last week to make some home-made bread. Used my favorite bread recipe: asiago-rosemary bread. One of the best things for relaxation is spending ten minutes kneading bread. This is what I've never understood about the fancy Kitchen Aid mixers that do the kneading for you--the machine does the best part!

Overall I've been pleased with the balance I've reached in residency. Despite working right at 80 hours per week, I've been able to exercise a little, attend church, read for work, and do some fun reading, as well as spend time with friends. As I look out the window I see blue sky with cumulus clouds (see picture below, but substitute urban sprawl for the idyllic countryside).

I can't help but be in a good mood looking at this picture!

I can't help but be in a good mood looking at this picture!Oh, I watched Finding Neverland last night. (DISCLAIMER: Skip the rest of this paragraph if you haven't seen the movie.) While it was impressively done and had a great story, still I found myself disappointed with the fact that the marriage kinda fizzled. I was hoping for some sort of redemption there, but I guess Hollywood values the romance of James' emotional intimacy with the Davey family more than the boring task of restoring a marriage. However, the movie did reinforce number 7 on my "Things to do in Life" list: Live in the countryside of Scotland for a year. During that year I plan to drink a lot of tea, do some gardening, go for daily strolls, attend a little Presbyterian church, and read plenty of good books. In fact, this may have surpassed number 6 on the list: Be a small-town volunteer firefighter.

Thursday, July 28, 2005

Answer to "Ask Marilyn"

So this puzzle was evidently designed to lead the intuition away from the cold, hard facts of statistics. After she explained what I'm about to explain, I'm told Marilyn had angry college math teachers and statisticians writing in telling her it was time to admit she was wrong. However, I stand by Marilyn.

To properly analyze this puzzle, we must first realize it is all about probability and statistics. It is just a little more complicated than asking, "If I flip a coin, what's the chance of getting heads?" but to understand the puzzle we have to remember the difference between an independent event and a dependent one.

Two independent events are, in fact, independent. I might ask, "If I flip a coin and roll a die, what's the chance of getting a heads and a six?" The chance is 1/12, which is equal to 1/2 chance in flipping heads, and 1/6 chance in rolling six. These probablities are multiplied as they are independent events.

So going back to our goat & Porsche problem, the chance that the Porsche is behind any particular door is 1/3.

1. Porsche ~ goat ~ goat

3. goat ~ goat ~ Porsche

1. Porsche ~ goat ~ goat

2. goat ~ Porsche ~ goat

3. goat ~ goat ~ Porsche

Wednesday, July 27, 2005

If one is good, then two is better...

A rectal exam is just what it sounds like, performed with a lubricated gloved finger. It yields information about sphincter tone, the shape and texture of the prostate, and if there's stool in the rectum. A guaiac test is a cheap and inexpensive way to assess for hidden blood in the stool. And finally a tilt test, which takes about 4 minutes, is done by taking the patient's blood pressure and pulse while supine, sitting, and standing. The results of this test give a clue to the patient's blood volume status.

"I'd be happy to do those things," I told Clay, thinking it would mean we'd eat sooner. After seeing the patient, doing the tests, and bringing him a warm blanket, I dropped off the guaiac card at the nurse station and returned to the doctor station to find Clay and my resident. They were gone! While looking around for them, I noticed the patient's door was shut, even though I'd left it cracked open. There was Clay, performing yet another rectal exam on this poor patient!

Clay later told me he thought I was kidding when I volunteered to help.

Tuesday, July 26, 2005

Ask Marilyn

Here's one math puzzle that I recently came across.

Suppose you are on a game show. There are three closed doors,

and the host tells you that behind two of the doors are two goats, and behind one of the doors is a brand new Porsche. If you select the door hiding the Porsche, you leave with the car. If you pick one of the other two doors, you get a goat. You are told to pick a door, which you do. Let's say you pick A.

Instead of opening the door, the game show host, knowing where the Porsche is, opens one of the doors you did not select to reveal a goat.

He then tells you that you can either stay with the door you originally picked (A), or you could switch your selection to the other door which remains closed.

Unfortunately you've already used your "eliminate an answer" lifeline. Your Aunt Nelda, the math teacher, is away from her phone. (Another lifeline burned.) Your last lifeline, the audience poll, shows :50% say to stay with the door A, 49% say to switch doors, and 1% say, "If you randomly pick a shirt and tie from your closet, what's the chance that their colors would exactly match?"

What do you do, and why? I'll post Marilyn's answer on Thursday.

Colorful captions...

"Approaching Heart Failure from a Cardiovascular Point of View," a talk to be given by Dr Inderjit Anand, Professor at University of Minnesota College of Medicine. This should be much better than that "Heart Failure from a Podiatric Perspective" talk I heard last week.

Monday, July 25, 2005

My grammar soapbox

I had the idea for this post when I heard this phrase in a presentation today, "This is a stigmata which indicates poor prognosis." It seemed ironic that the speaker would choose a relatively obscure and erudite plural form (stigmata, similiar to how data is the plural of datum), but then proceed to egregiously mismatch the singular indefinite article, a.

Did I call him down in the middle of the presentation? No, though such an action may be justified given the blatant offense. One error which I have, of late, begun to gently correct is the pronunciation of height with a "th" at the end. "Width" and "breadth," but "height."

And for the richness of colloquial diction, I fully support the term, "the sugar diabetes," especially when the word diabetes ends with a short i vowel sound rather than a long e.

For the one reader who has continued this far, I have a question. When there are two people who possess one thing, how is this correctly indicated? Is it "Dick and Jane's dog," or "Dick's and Jane's dog"?

Sunday, July 24, 2005

For the Love!

"...And on Tuesday, senators from Oklahoma and Iowa filed legislation to close Love [Field], potentially forcing Southwest Airlines Co. to move to Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport, where American Airlines Inc. dominates."

What on earth is this counter-legislation? A bill, of course supported by Southwest Airlines, to repeal the Wright Ammendment is introduced, and now weeks later, two senators (from OK and IA of all places!!!) file to close Love Field. Many questions are in my mind, first of all, what business do these senators have to file legislation to close an airport in a different state? This seems absurd.

Secondly, in the article "Dueling Senate bills carry risks for Southwest--and for Dallas," we see American Airlines now clamoring for gates at Love Field should the Wright Ammendment be repealed. Of course, this would be fair...it's the free marked Southwest has been pushing for all along. But it still seems a bit childish of the largest airline in the world to attempt to stifle Love Field, but then to want to move in and open up flights. Childish, and an impressive display of corporate muscle at the same time. "If we can't have our way, then we'll drive you out of the Dallas market, just as we did with Legend, JetBlue, etc," AMR seems to be saying.

You can read more thoughts on my friend, Doctor J's, blog. If anyone has a different perspective on this issue or any rational explanation for the bill co-sponsored by the Oklahoma & Iowa senators, I welcome your comments.

Saturday, July 23, 2005

Okay....now the war in Iraq

I'm a little puzzled that Betty Schroeder, 74, who otherwise seems well informed about current events, didn't realize that she was simply too old to join the military. And while I admire her patriotism, I worry about her strength and stamina in those harsh conditions.

Just for fun...Election 2004

- Schiavo controversy--done

- Election 2004--read on in this entry

- War in Iraq--not going to cover this

- Midwest Farmers' Union v. the State of Iowa (the Great Corn Scandal of 2002)--yet to come!

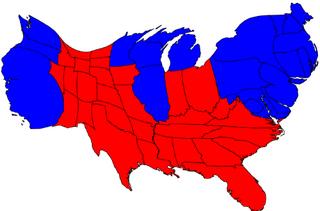

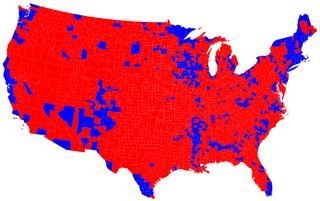

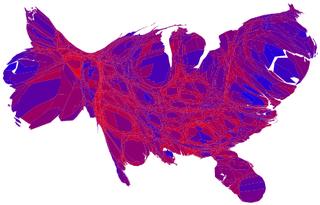

Anyway, it's 1:45 in the morning, and without further ado, here are a few comments on the cartograms produced for the 2004 election. These are great devices as they convey a large amount of information in visual form. Evidently there's a science behind the making of them, as it's difficult to adjust proportions without distorting the shape too much.

This first one represents the states' results (Republican, of course, being red, and Democrat, blue) as well as their relative representation in the Electoral College. Even though there are many more red states than blue, the surface areas are approximately equal. This is because the blue states, on average, are larger in terms of population and hence have more representatives in the House.

I thought this next one was impressive. It shows the USA divided up county by county. (Apologies to Alaska and Hawaii.) In contrast to the first cartogram, this one emphasizes how the blue areas tend to be focused in major metropolitan areas. I can see LA, San Diego, San Francisco, New York, the entire state of Massachusetts, Miami, etc. Knowing that the popular vote wasn't far from 50/50, this map also tells us that as a whole, the red counties have a much lower capita per square km.

This one's my favorite. You may have thought it's a topographical map of Burma. In fact, it shows the United States divided up county by county, with a continuum of color. For instance a county that went nearly 100% Democrat would be blue, 100% Republican would be red, but most are a mix--hence various shades of purple. In addition, the counties are shown sized in proportion to their population. Again, we can see San Francisco on the west coast, as well as gigantic LA and Orange Counties. On the east coast, notice how large Long Island is. And Cook County is clearly visible just boardering Lake Michigan.

Friday, July 22, 2005

From Quinlan to Schiavo...

The first half of the talk was on distinguishing between different types of profound brain injuries.

Coma is understood as "eyes-closed unconsciousness." It is rarely permanent, is the most common initial presentation of severe brain injury, and may progress to...

- complete recovery of neurological function

- recovery with some remaining deficit

- the "locked-in" state

- a minimally conscious state

- permanent vegetative state

- brain death

Brain death, however is permanent. This term indicates the irreversible loss of the clinical function of the entire brain. Not only can a brain dead patient not think or be aware, these folks can't even breathe on their own. In other words, it's a state made possible by the technology of mechanical ventilation. Interestingly, it was first postulated in 1959, and criteria to define brain death was first developed in 1968 in order to have grounds for transplanting organs from a person whose heart was still beating.

The vegetative state can be thought of as "eyes-open unconsciousness." It's argued that like brain death, the vegetative state is a result of modern medical science's ability to keep the body alive through various means. In this state, there is a lack of integration between parts of the brain. Because the upper brain does not receive or send information, there is a "dissociation between being awake and being aware." In these patients, however, the brain stem is generally intact, so they breathe on their own, the heart continues to beat of course, and most reflexes should still be intact (e.g., the reflex to swallow when food is pushed to the back of the throat.) Virtually all neurologists agree that patients like Karen Quinlan and Teri Schiavo were in a permanent vegetative state.

Recovery: Too, it may be important how a person entered the permanent vegetative state. Was it due to trauma or due to a metabolic insult to the brain? It should be noted that there are no cases reported in the entire body of medical literature of a person recovering from a permanent vegetative state--caused by anoxic brain injury--after a duration of 2 years.

Finally, there is an additional condition called the locked-in state. In this case, consciousness is preserved, but the person is completely paralyzed except for eye movement and blinking. The Diving Bell and the Butterfly: A Memoir of Life in Death by Jean-Dominique Bauby is a book written by a man in just such a condition. He dictated the book letter by letter with the assistance of an aide. More information can be found here.

Anyway, I hope you find this information helpful. It is certainly just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to thinking of the ethical issues involved in a case like Schiavo's, but it may be useful for thinking more clearly and speaking more intelligently on such things.

By the way, I'd like to credit my source of this information. It comes from a presentation by Robert L. Fine, MD, FACP, Director, Office of Clinical Ethics, Baylor Health Care System, Dallas; Director of Palliative Care, Baylor University Medical Center.

Thursday, July 21, 2005

Emily's been writing again...

I think in ways Emily Dickenson reminds me of my grandmother, Joy. Joy loved reading, and even though she never traveled much farther than from Kansas to Chicago to Texas, the expanse of her mind was vast. Those of us who have had the privilege of traveling the world would probably do well to remember Emily in her quaint quarters, with her hundreds of posthumously-published poems tucked away in the little ebony box under her bed.

I really enjoy the apparent simplicity of this poem, and the second stanza is unquestionably brilliant. (Note again the presence of approximate rhyme!)

To fight aloud is very brave,

But gallanter, I know,

Who charge within the bosom,

The cavalry of woe.

Who win, and nations do not see,

Who fall, and none observe,

Whose dying eyes no country

Regards with patriot love.

We trust, in plumed procession,

For such the angels go,

Rank after rank, with even feet

And uniforms of snow.

Wednesday, July 20, 2005

An update...

I sat down and visited with them for several minutes. I think some of the other doctors had conveyed some hopeful signs to the family earlier in the day, so they seemed as calm and collected as I'd ever seen them before! We talked some about the medical plan, and then I inquired into some of their personal thoughts and plans. At the end of the conversation I offered to pray with them, which they readily accepted.

As I left the room, all three of my "patients" repeatedly thanked me for visiting with them and praying with them. (This included the patient's mother, who a few days earlier had insisted on seeing the chief resident!)

Sure, it's a little daunting to be the intern on a medical care team comprised of a seasoned internist, a pulmonologist, a gastroenterologist, and a cardiologist; especially given that I'm only a month or two out of medical school, and the ICU nurses know much more than I about managing unit patients. But I realized that today I did for this family what no one had previously done, including the psychiatrist who had been by a couple times to "support" the family. I was able to be a physician in a broader sense, treating the family as well as the patient, and addressing spiritual needs along with the physical. That was really exciting!

Tuesday, July 19, 2005

Conspiracy theory

Although I was initially annoyed by the encounter, it got me thinking, "Maybe the government really does cover things up. I mean, look at Roswell." I did some searching on the internet, and found some sites presenting solid evidence for just such a thing. Although this site was obviously designed by an amateur, the research is substantial and the argument compelling.

Saturday, July 16, 2005

A bad case of pancreatitis

Other plans were in store. I know something was amiss when I went to my 33-year-old patient's room. This was a young man who came to Texas last week with his family, trying to avoid the hurricane that hit the gulf coast. He had acute pancreatitis from alcohol use, but he seemed to be on the up-and-up so to speak. When I opened his door this morning, however, I saw his neatly made bed which was raised up high and the room was otherwise spotless. His chart was gone. Something was wrong!

When I checked back at the nursing station, the doctor on call last night told me the patient had had a run of SupraVentricularTachycardia, which essentially means his heart is beating too fast, but the electrical conduction system from the atria to the ventricles was working properly. He'd been transferred overnight to the telemetry unit and his heart slowed down with a couple medicines--adenosine and diltiazem. He was also started on a whopping antibiotic--Imipenem/Cilastatin to treat for possible infection which was suspected when he spiked a fever.

After talking with the cardiologist, I evaluated the patient, and then was intercepted by his mother in the hall. Understandably she was upset and full of questions, but the combination of the two made the encounter particularly unwieldy. I found myself trying to answer her questions and realizing she was asking the same thing all over again. The conversation ended in her frustrated and tearful exclamation, "I need to see a real doctor! Where's the chief resident?"

When it was all said and done, my patient was transferred to the ICU, where he was later intubated and put on the ventilator after his Arterial Blood Gas (ABG) showed that his muscles of respiration were fatiguing. The gastroenterologist saw him today, as did the cardiologist, the pulmonologist, surgeon, and the attending internist. I think it's safe to say we have plenty of people on board, and fortunately the patient was stable by the time I left.

Perhaps one of the most important things I did today (out of nearly eight hours at the hospital) was to spend 15 minutes visiting with the family, trying to support them and answer any question they could think of. Still, the day's work left me a little dazed with how someone--young at that--could be doing so well one day and then intubated and being managed by multiple specialists the next.

Thursday, July 14, 2005

Mission: accomplished

The first order of business was reinvestigating the rooftop trapdoor. After making sure the coast was clear, we climbed the ladder on the top floor of the hospital and pushed open the trapdoor, which sent sunlight streaming down to the landing. We gingerly climbed out and surveyed the scene. The roof of the hospital was made of a soft, gray tar-like substance, and the view it afforded impressive. On a clearer day the sight would have been even better.

Looking south, one can see the center of this metropolitan center. A few of the major freeways coursing through town are readily observed, and a lake is just within view. The rooftop itself has a cluster of radio antennae, and a pleasant breeze greeted us as we basked under the vast Texas sky.

Okay, so the picture above isn't really the view from the hospital. But 10 points to the first person who can leave a comment with the name of the university that sits in the background, to the right of the smaller body of water. Hint: Listen my children, and you shall hear...

By the way, I thought this article was hilarious!

Tuesday, July 12, 2005

A rediscovered gem

Just for fun, I did a quick Google search for the following text which I arbitrarily selected: "I just wanna praise..." The search unearthed what I call Exhibit B. This appears to be a song of the "Praise and Worship" genre; it is the chorus from a larger composition entitled Thank You by The Katinas.

Exhibit A

I'll praise my Maker while I've breath;

And when my voice is lost in death,

Praise shall employ my nobler powers.

My days of praise shall ne'er be past,

While life, and thought, and being last,

Or immortality endures.

Happy the man whose hopes rely

On Israel's God! He made the sky,

And earth, and sea, with all their train.

His truth forever stands secure;

He saves the oppressed, he feeds the poor,

And none shall find his promise vain.

The Lord gives eyesight to the blind;

The Lord supports the fainting mind;

He sends the labouring conscience peace;

He helps the stranger in distress,

The widow and the fatherless,

And grants the prisoner sweet release.

I'll praise him while he lends me breath;

And when my voice is lost in death,

Praise shall employ my nobler powers;

My days of praise shall ne'er be past,

While life, and thought, and being last,

Or immortality endures.

Exhibit B

so here i am

with all i have

i raise my hands to worship you

i wanna say thank you

oh, thank you

for everything

for who you are

you covered me you touched my heart

i wanna say thank you

oh, thank you

Monday, July 11, 2005

Animals beginning with the letter "X"

Lori was at a loss, however, to find an animal whose name begins with an "X," so Clay searched the internet today. When I saw what he came up with, I laughed so hard I felt nauseated! This is a Xenamorph, i.e., a combination of Xena and Morph.

Sunday, July 10, 2005

My bedside table

I've never really been one to read in bed, since by the time I go to sleep, I'm usually quite tired. But my roommate David, who suffers from intermittent mild insomnia, is a big fan of the practice, so I've decided to start. My first book to keep at the bedside is a book of Emily Dickenson poetry. (My old college English teacher, Professor Miller, would be pleased. Her literary triumvirate of unparalleled greatness consists of Dickenson, Anton Chekov, and W.B Yeats.)

Here's one of Dickenson's I ran across last night.

Success is counted sweetest

by those who ne'er succeed.

To comprehend a nectar

Requires sorest need.

Not one of all the purple Host

Who took the Flag today

Can tell the definition

So clear of Victory

As he defeated--dying--

On whose forbidden ear

The distant strains of triumph

Burst agonized and clear!

This raises several questions in my mind. First of all, there's poor frail Emily in her starched and rather uncomfortable puritanical garments sitting at her window overlooking a side street of Amherst. What sort of game was she envisioning that involves a team (dressed in purple at that) capturing a flag? And the loser was dying? Come now, Emily!

Then again, maybe this was this a purple-clad army. This could be more plausible, and it actually paints a rather vivid image.

The other thing about Dickenson is that almost all of her poems could be sung to the tune of "Amazing Grace." There's the horrible temptation to read them aloud, emphasizing each iamb and pausing at the end of every line. This is dreadful. Try reading the above poem out loud, ignoring the lines and treating the punctuation just as a person might say the words in prose. It's much more enjoyable!

One last thing I love about Dickenson is her use of approximate rhyme. For example, note the pairing in the second stanza of today and Victory. This gives the diction a richness that strict rhyme would preclude.

Call Day #3

- Chatted with the other interns who are here today. Also worked on comprehending the creatinine clearance formula, making sure I can cancel all the units.

- Seen my two patients with whom I'm coming into call.

- Explored. The tenth floor of the hospital is a smaller floor, only having four call rooms for residents and a conference room. Hence, there are doors on either end of the central hallway which open onto the roof. This would be ideal for sitting in the open air watching a sunset in the vast Texas sky. Unfortunately one of these doors is locked with a wimpy doorknob lock, and the other appears to be connected in with the hospital's fire alarm system.

- Done further exploration: a lone staircase on the tenth floor leads up to the eleventh floor, of which only a small landing is accessible. A door with a "High Voltage warning" greets visitors at the landing. The door is, of course, locked, but through a window in the door one can observe a large mechanical room with generators and pipes. Of great interest, however, is that there's a ladder leading up from the landing to a trapdoor in the roof. Of primary concern is whether this trapdoor, too, would set off the fire alarm. Careful inspection would indicate no. Around this point in my investigation I became a little antsy, so I'll update you in a future post about this trapdoor and its implications for sunset-watching potential.

- Written two thank-you notes.

- Discussed the 401(k) plan with the other interns. Sadly, it would appear that one-year employees are not vested at all for matching contributions.

Wednesday, July 06, 2005

Code blue!

I dropped my pen without even signing the order and jogged to the stairs, up one flight, and to the patient's room. Even with my recent Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) training, I was hoping to see at least one white-coat clad person in the room. There was none. The room was crowded with nurses and resipiratory therapists (RTs) already. In the flurry of activity, I tried to slow my racing mind, steady my shaking knees, and review the ABC's (Airway first, then Breathing, then Circulation) I'd been taught.

Working my way toward the patient's bed, I observed RT's mask-bagging the patient already and a nurse performing chest compressions. In my training protocols with dummies, I'd practiced codes from the start. Where to start here? The initial ABC's seemed to be already in place. I asked the nurse to hold compressions while I checked the pulse; meanwhile two other interns entered the room and one handed me gloves.

No pulse. "Resume compressions," I instructed the nurse as I donned the gloves. Still trying to think, I realized I needed to get a heart monitor on the patient. The resident's appearance at the door brought a sense of relief. Chest leads were applied. "Let's get this guy intubated!" the resident instructed, "Jonathan, you're up!"

At the head of the bed I felt much more comfortable after having had a few months of anesthesia training. "Doctor, what size tube? 8.0 or 7.5?" If I'd had time to think about it, I'd have requested an 8.0 endotracheal (ET) tube, the size typically used in male patients in the operating room. "I'll use a 7.5," I said without hesitation, simply picking a number and trying to hide my nervousness with a confident tone of voice. "Oral airway, please," I requested, when I realized the RT was having diffulty bagging the patient.

"Ready?" my resident asked. Another RT had just lubricated ET tube and placed the cold, metal laryngoscope on the sheet beside the patient's head. I opened the tool's blade, checked that the light was working, and removed the patient's upper dentures. This was going to be the easy part...

In the meantime the defibrillator pads had been placed. The monitor showed PEA, which is Pulseless Electrical Activity of the heart. The heart, in other words, was barely attempting to beat, but was not effectively moving blood. ACLS protocol is to give epinephrine for this cardiac arrhythmia. No dramatic shock was necessary.

Meanwhile, Clay and my resident had been working on starting a central line for venous access, through which to give the epinephrine. With a thready pulse from the CPR, finding the femoral vein by approximating its location medial to the femoral artery was nearly impossible. Instead, multiple well-placed jabs with a syringe proved to be the most effective technique.

Steading my left hand and applying pressure on the laryngoscope toward the foot of the bed, the vocal cords came easily into view. I grasped the tube at the end and watched it slide between the cords. An RT inflated the cuff on the interior end and my resident listened for breath sounds as another RT began bagging. "No breath sounds. You're in the esophagus."

I withdrew the tube, surprised since it had seemed an easy intubation. Another attempted yielded the same results, though the chest appeared to rise and fall with bagging. Another senior resident stepped in. After his intubation, still no breath sounds were heard. It was decided that with all the patient's respiratory secretions, airflow was difficult.

Three or four doses of epinephrine were given as CPR continued. I reached again to check the patient's radial pulse. His had was cold and clammy. The nurse performing chest compressions had tired, so I took over. There was little resistance to my effort as the patient's ribs had certainly cracked. I performed steady compressions for a few minutes. By this time, CPR had gone on for 20 minutes, with no response to the epinephrine. The attending physician had appeared, and since the room had quieted down since the initial rush, it was easy to hear his implicit instructions, "I think we've done everything we can do."

Everything suddenly seemed to stop. The RT stopped bagging. A few people left the room. And I ceased my compressions, stopping bloodflow to this patient's brain, lungs, and heart. He was dead.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Turning back for one last look before I left the room, I saw the patient's cast on his left arm. He was a gentleman in his 70's who had been admitted for a broken wrist. That was it. This patient's hospital course was not filled with dire straights. He'd simply had a broken bone and it had been set in a cast. And his heart had suddenly stopped, likely due to a massive blood clot to his lungs, called a pulmonary embolus. Cancer, strokes, pneumonia...these diseases kill in a matter of days to weeks to months. In this case, however, death came in seconds even though everything that could have been done had been done.

Later that morning I heard that this fellow's wife had arrived. This reminded me that he hadn't lived his entire existence in his hospital room. He was a husband, and likely a father and grandfather. Even though we'd never met before, I knew he had a story. But for a mere thirty minutes in that raucous room filled with shouts, blood, and the incessant rhythm of compressions, our story was our lives intersecting in one violent finale. And then it was over. The music stopped. We picked up our coats, gathered our things, and went on our way.

Monday, July 04, 2005

Contemplations on life and death

In this poem, Billy Collins wanders from room to room in his house, musing which room would be the most fitting in which to die.

I will quit these dark, angular rooms

and drive along a country road

into the larger rooms of the world,

so vast and speckled, so full of ink and sorrow--

a road that cuts through bare woods

and tangles of red and yellow bittersweet

these late November days.

And maybe under the fallen wayside leaves

there is hidden a nest of mice,

each one no bigger than a thumb,

a thumb with closed eyes,

a thumb with whiskers and a tail,

each one contemplating the sweetness of grass

and the startling brevity of life.

Of note, I have my good friend Matthew to thank for introducing me (in the literary sense) to Billy Collins. I have yet to meet him in person, but my autographed copy of Picnic, Lightning is a treasured possession!

Phones, pizza, and prayer

I also showed a rather embarrassing display of poor phone etiquette today. Clay and I were at a nursing station, sitting across the desk from each other, working on discharge paperwork. I told Clay I was calling one of our attendings—Dr M, and asked if he had any patients to run by her. He’d been trying to page a neurologist and was unsuccessful thus far. Clay said that yes, he’d like to speak with the attending after I did. Very soon after paging, the phone rang. The unit clerk announced, “Did anyone page Dr L?” who happened to be another of my attendings. I said, “I did not, but I’d like to talk to her.” No one else spoke up, so I picked up the phone, and out of the corner of my eye I saw another nurse shuffle off to look for whoever paged Dr L. After discussng one patient with the attending, I heard the clerk announce that Dr M, the other attending who I had paged, was calling back. I asked Dr L if I could finish up with her later, and hung up the phone just in time to see the nurse arrive with another nurse who HAD paged Dr L! They gave me a look which was a mixture of annoyance and amusement! I offered a look of helpless apology and then answered the phone line with Dr M. After quickly discussing our patients, I hung up. Just then, Clay sighed and said, “I needed to talk to her too!” I apologized to him, and went back to my note-writing. The thought crossed my mind that I needed to make one more page, so I reached for the phone. In the split second before the phone left the cradle, it began to ring. I held the phone up to my ear, didn’t hear a dial tone, and returned it to its cradle. This all took place in the span of 2 seconds, which was not enough time for my mind to register that perhaps this phone automatically answered the ring, and perhaps this was Clay’s neurologist finally calling back. Both of these un-supposed suppositions were true. In a matter of five minutes, I’d hung up on the attending returning a nurse’s page, didn’t give Clay a chance to talk to a different attending, and then inadvertently hung up on Clay’s neurologist!

After finishing my work, I grabbed lunch with Clay and another ophtho intern Mark. Today's lunch consisted of a personal size vegetable pizza and coconut cream pie. The lunch was redeemed by the fact it was a vegetable pizza, as well as the accompanying skim milk and banana. My last task of the day was to dictate for the first time at this hospital. I journeyed down to the basement Medical Records office since I needed the patient’s chart with its H&P. There I stumbled through my anything-but-eloquent-and-concise dictation and swung by the O.R. to pick up some scrubs. On my way out of the hospital, I stopped and remembered my stroke patient. I returned to the third floor and visited with the patient’s daughter-in-law a few minutes. I mentioned, “I heard your niece say that you all are hoping and praying for the best. Are you people of faith?” In my somewhat round-about question, the daughter-in-law understood I was asking about church and said that the patient was sad to miss church a week ago. When I asked where she went to church, the daughter-in-law said that it was a Korean church. “Presbyterian?” I asked. Yes, it was. At that point, I offered to pray with them, and a look of gratitude passed over the daughter-in-law’s face. As I sat in the chair next to her, she turned to her mother-in-law and spoke a few words in Korean. The patient, much more alert than I’d seen her before, looked at me, extended her hand to hold mine, and said in English, “Thank you.”

This was another one of those moments in which I realized and experienced the amazing privilege of practicing medicine. Here was a patient who was sitting on our service; we could do nothing to improve her stroke and could only offer preventative care. But this was a real and a definite opportunity to be a healer, and a moment, I hope, of grace.

Sunday, July 03, 2005

My first call: Home again

A three hour nap at home awaited me, followed by dinner with a few friends at a nearby restaurant.

We followed that with a few rounds of Balderdash. One of my most creative and believable (so I thought) definitions was for a word temblor, which actually means trembling as in an earthquake. Reminded of the word tenebrous, I scribbled my definition: “a mood or aura characterized by shadows and mystique.” Perhaps it was the small glasses of Bailey's we'd enjoyed, or perhaps it’s true that people are funniest when they aren’t even trying, but the room exploded with laughter when my definition was read! Everybody immediately know I’d written it!

We finished the evening with a quick trip to the top floor of the parking garage where we could see the fireworks that the city put on just west of downtown.

My first call: Rounds the next morning

Then there was my patient who’d had a stroke. One week before admission, she’d been functional, able to care for herself, cook for herself, etc. This Asian woman had had a stroke in her cerebellum which affected her ability to walk and her coordination. Not so bad, really, considering what could have happened. My impression is that on the day of discharge (July 1st), she was still able to walk with a walker, and was totally lucid. She had perhaps a little difficulty with using her left arm. And she was not anticoagulated since the stroke had converted to a hemorrhagic one. But then the night prior to admission, she’d fallen in the bathroom while her daughter was trying to assist her. It was more of a slump than a slip. She’d bumped hit her head on the tile wall. The daughter walked her back to bed, but then noted some hours later that her mother was disoriented, not responsive, and staring constantly to the left. At this point they brought her in to the hospital, one day after she’d left. She would mumble some unintelligible words, and could barely move her extremities.

While making my rounds, I walked into a room full of people. Daughters, sons-in-law, granddaughter…all had come to be with this matriarch. And with tearful, expectant eyes, they looked up at me (one month into officially being a doctor and two days into my new job) and began pouring out their questions in broken English. “What happened?” “What does the MRI test show?” “Will she get better?” “Did her fall do this?”

The last question was the biggest challenge. Even though I wondered if there was some possibility that minor trauma could lead to an embolus coming loose and causing an ischemic stroke, I thought in the elderly a bump to the head would more likely result in a subdural hemorrhage or something of the sort. More importantly, I realized that the patient’s daughter was in a position to blame herself for her split second of inattention during which her mother fell. Even though it may have been technically correct to say, “Will you please wait a minute while I go look that up?” or “Why don’t you ask the neurologist when he comes by?”, I believed, and still believe, that at that moment it was more important for me to go out on a limb. I’ve had four years of medical school for a reason, and I think that gives me some grounding for spontaneous answers that I can’t back up right away with statistics and figures. In this case, my role was not statistician but healer. I looked the daughter in the eye, and slowly, such that she could understand in her limited English, I told her, “No. I don’t believe the fall caused your mother to have a stroke. There was nothing that could have prevented that stroke. I know you hate to see your mother this way, but I can tell you she is one fortunate woman to be surrounded by all this family that loves her.”

Rounding next brought me to my elderly patient with the UTI and suspicious cardiac enzymes. The nurse met me at the nursing station.

“Doctor, are you taking care of Mrs. C?”

“Yes, I am.”

“Could you do something? She’s really agitated!”

I paced over to her room, hearing noise through the door. Upon opening it a sight met my eyes. There, attempting to restrain a feisty, naked, and agitated 92-year-old were a nurse and an assistant. “I’ll write some orders,” I said, turning on my heels.

“Make it intra-muscular!” I heard behind me. “She’s pulled out her I.V.!” This time, it was “Haldol 2mg IM” I wrote in her chart. Multiple shifts in the psych ER proved beneficial in this case. I reviewed the patient’s vital signs and nursing notes at the nursing station, and ten minutes later, she was lying clothed and tucked into bed, peaceful and cooperative when I went in to see her!

My first call: Calls in the night

In the meantime, I was paged a nurse who was concerned about my patient with hyponatremia. The day before, some blood was noted in his Foley bag. We figured this demented fellow most likely had tugged on the catheter, leading to hematuria. I discontinued his aspirin and Lovenox to help the blood coagulate at the site of trauma. However, the bleeding continued. We began measuring his hematocrit every six hours. And by this time, the night of Day Two in the hospital, his hematocrit had dropped nearly 10 points. Even the budding anesthesiologist in me felt ready to transfuse. My resident agreed, so I wrote the orders. The nurse, however, realized we didn’t have consent on the chart. I called the patient’s daughter who had medical power of attorney and left a message at her contact number, to no avail. Same with her cell. Called both numbers again with no response. The nurse called the nurse manager, and together they stood firm about not initiating the transfusion without proper consent. Given that the patient was alert and oriented, comfortable, and had stable vital signs, I began to question the need to transfuse at 0200. (It should be noted that my phone message to the patient’s daughter was carefully crafted so as not to worry her.) We’d keep an eye on him, and in the morning transfuse after consent. I ran this plan by my resident, who disagreed. This was a medical emergency: we needed to transfuse, he said. I quickly realized that the nurse and her manager were flat out refusing to transfuse. I felt myself leaning toward their side, so I made the decision to call my own attending. Our conversation went something like this,

“Hi, Dr. ______ , sorry to wake you. I was calling about Mr. _______ , our 73 year old with….” “Just tell me the facts. What is it?”

“His ‘crit is dropping. We need to transfuse, but we don’t have consent and can’t reach his family.”

“Is he stable?”

“Yes, he’s alert, oriented, and his blood pressure and pulse are fine.”

“Then we can’t transfuse without that paper on the chart.” [pause]

“Okay…thank you.”

I felt a sense of relief. I’d been caught between my resident and the nurses, agreeing with the need to transfuse, but also recognizing the ethical delimma. My attending, brusque as she was, backed me up. And the stat H/H I ordered showed the blood count was stable for the last four hours. Several lessons learned.

- Get consent before it’s needed. (Think ahead!)

- Be aware when you’re in an ethical crisis. If something feels not-quite-right, it probably isn’t.

- Learn to stand up to your superiors. For me, this may have meant reasoning with my resident, and trying to convince him not to transfuse.

- Even in gray areas, do your best to do what is right. There are risks associated with transfusion. One anesthesiologist I know made sure all students were aware of this. In the case of this cheery, demented fellow who was happy to get the transfusion, I knew he really wasn’t able to give informed consent. And I knew it wasn’t a true emergency, given his stable vital signs and mental status.

- And even when nurses seem to get in the way of practicing good medicine, step back and evaluate the situation. They may have a good reason.

I’d crawled into bed and dozed for thirty minutes when I heard two beeps. I fiddled with my cell phone (on which I’d set the alarm), annoyed that it was beeping. Only then I realized that the beeping was my pager. I’d been paged a couple minutes before and slept through it. This time it was a nurse taking care of my elderly woman with the UTI. At the recommendation of my attending, we ordered three sets of cardiac enzymes and serial EKG’s on her to evaluate for MI. The reasoning is that the elderly often don’t complain of chest pain with an MI, and this is a big cause for medical liability. In other words, ordering a few labs can prevent a big lawsuit. This nurse was telling me that the patient was on the floor. (I must have written an order, “Please call M.D. when patient arrives to floor,” or something of the sort. It’s all hazy now.) In any case, this reminded me to check her second set of cardiac enzymes. The first set had shown just a mild elevation of the nonspecific CK enzyme. I napped a few more minutes, and then got up to check the labs. The CK was even higher, and the MB portion (specific for damaged heart muscle) had creeped up into the abnormal range. Great. Do I need to start her on aspirin, a beta-blocker, oxygen, and nitrates? I really wasn’t that worried, and I debated about calling my resident. I called the nurse back and ordered aspirin 325 mg PO, first dose now. Since the troponins (sensitive for heart damage) weren’t elevated, I felt pretty sure she wasn’t having an MI. I crawled back into bed, and thirty minutes later was paged again.

“Mr. W’s sugars have dropped to 135.” It was an ER nurse calling about my severely hyperglycemic patient. We’d wanted him to go to the step-down intensive care unit since patients can develop electrolyte abnormalities with big changes in serum glucose. Unfortunately, neither the ICU nor the step-down unit had beds available, so we left him the ER. The goal was to bring the sugars down slowly with a small but steady insulin drip. In this patient with poorly controlled diabetes, however, his body must have been extremely sensitive to insulin. His sugars plummeted. I asked the nurse to draw a stat electrolyte panel. At this point I called the resident and told him about both situations: The elderly woman’s cardiac enzyme panel, and the dropping sugars. He told me to talk to the attending, ASAP. In sharp contrast to my previous encounter with her, she seemed awake and even chipper. She was down in the ER, and had seen the patient. His stat labs were back, and his electrolytes were fine. She was actually quite happy with his progress. And she agreed with me. The former patient was not having an MI. No need to start additional medications. I thanked her, and crawled back into bed for the third time, with thirty minutes to sleep again. After a quick shower at 5:45—which does amazing things to make a post-call doc feel civilized—it was time to round.

Saturday, July 02, 2005

My first call, continued

- An older gentleman with his first MI and subsequent atrial fibrillation.

- An older woman with a retroperitoneal abscess and MRSA. She also suffers from dementia and/or delirium.

- An elderly man with hyponatremia and an AKA.

- An older woman with a stroke.

- An elderly woman with a GI bleed.

- An elderly woman with a UTI and possible pneumonia.

- A middle aged man with uncontrolled diabetes and a serum glucose of >900.

My first call

Again, I awoke before my alarm feeling a little nervous. After a little tossing and turning, I eventually decided to go ahead and shower. The night before I’d thought ahead and packed an overnight bag. It contained:

- A fresh tee-shirt and boxers

- Clean socks

- Toiletries (though I left the razor and shave cream at home…if there’s anytime a man deserves a day without a shave, it’s a day after a night without sleep!)

- Spray shoe freshener. This is essentially spray deodorant designed for shoes. I suppose any spray deodorant would work, and would probably be cheaper. With my small closet at home with eight pairs of shoes inside, I feel better about not polluting the limited airspace with musty aromas.

I also thought it would be good to bring some reading material, in case it was a slow call day. As usual, I totally overestimated the amount of free time I’d have to read. In any case, armed with these books I marched into my first call:

- Massachusetts General Hospital's Pocket Medicine. My copy is already annotated with helpful notes, such as how to properly analyze a patient’s acid-base status. (This one stays in my white coat, as does my palm pilot, and a pocket notebook in which to jot notes. And of course a pocket Pharmacoepia.)

- The Washington Manual Intern’s Survival Guide. This book’s a bit overpriced at $30 and essentially contains the bare bones of Pocket Medicine. However, it is a briefer read and has some witty comments.

- My new pager’s user’s manual. One of these days I’ll figure out how to use all the buttons.

- Billy Collins’ Questions About Angels. The beauty of poetry is that, much like a juicy grape or a cruchy Triscuit, you can enjoy it in a very brief period of time. Sure, steak and wine is nice on occasion, but my first call is no time to make an attempt at finishing Anna Karenina.

- Critical Care Handbook of the Massachusetts General Hospital. With an open ICU, I could always be admitting a unit patient.

- Clinical Anesthsiology, published by Lange. This book came with enthusiastic recommendations, and being at a private hospital training program which emphasized “reading time,” I’d like to make my way through this book over the next 12 months. At approximately three pounds, this is a literal heavy-weight, but well worth reading potential.

- Felson’s Principles of Chest Roentgenology: A Programmed Text. A slim book which reviews chest radiographs. In the time since radiology rounds as a third year medical student on internal medicine when I asked a radiologist what exactly a roentgenogram was, I’ve become much more comfortable with this esoteric, even archaic word. It seems to harken back to the golden days of radiology, when simple x-ray technology was the best way to look at the mediastinum, and radiologists didn’t have to compete with Pulmonary docs in CXR expertise. In any case, it’s a rudimentary text which should be a good refresher, even if it doesn’t probe the extent of the implications of distinguishing between reticulonodular and ground glass patterns.

- Stationery, to catch up on the thank-you notes I need to write. These range from graduation gifts to a dinner with friends at their cozy apartment on Marquita Street. We had a bottle of Ruffino Chianti that night, which I believe we all enjoyed.

I don’t think I used a single item from this list. Perhaps that makes all the other interns feel a little better.

Friday, July 01, 2005

The Medical New Year

After morning rounds was a teaching conference, and then there was interns’ conference which was a continuation of orientation. I completed patient notes and orders in the afternoon, and then attended to a patient who was bleeding into his urinary catheter. On the way home around 4:00, I was called about a psychotic patient who became belligerent. I asked the nurse to give the recently-given Haldol a little more time, and then try Geodon (for which "as needed" orders were already written), then to page again if there were continued problems.

I parked on the street outside the apartment building and helped my roommate Dan load his bags into the car. He was flying home today for the July 4th weekend in Oregon. Since he's just finishing his third year of med school, he gets a three-day weekend!

After I relaxed and ate dinner at home, I was paged again for the patient who was bleeding again, now with decreased urine output. Most likely trauma from the foley in this demented patient. I formulated a plan, called the resident, talked to the nurse, and then called the page operator to tell her I was checking out! (I should have done this at 1700!) I also called the cross-cover intern to tell her what was up, thinking she might like to know should she be called.

I finished the day catching up on e-mail. Unfortunately no studying was done today, but I’m on call tomorrow so hopefully will have some time at the hospital! So this is it: the first step in a long journey of medicine!