So the theme of this post is EKG's. This is a story from last spring as a med student which was a little embarrassing for me, but a beautifully post-able story.

The time was spring, the place: the illustrious local VA hospital. The setting: I, a fourth year medical student who had already matched and was on his very last two weeks of rotations, was spending some time doing cardiac anesthesia.

Now, a word about cardiac anesthesia. If I were to ever drop dead with ventricular fibrillation arrest, I can think of no one I'd rather have around than a cardiac anesthesiologist. They take care of sick patients daily. They manage airways. They pharmacologically cradle and caress fragile hearts during procedures in which the heart is chilled, poked, prodded, torn apart, sewn together, or transplanted. They're quick on their feet and are good with trans-esophageal echocardiogram too.

Yes, trauma surgeons get their share of glory. And I would be remiss if I didn't mention OMFS. But still, we would do well to remember who keeps the patients alive while the surgeons do their work.

In any case, there I was, learning a lot of cardiac physiology but actually doing very little in this rather acute setting. Sure, an intubation here, an arterial line there. But the resident was eager to practice central lines, and thus I watched quite a few being put in.

Placing an internal-jugular central line begins with a well-placed needle jabbed into the neck. Avoid the carotids!

Placing an internal-jugular central line begins with a well-placed needle jabbed into the neck. Avoid the carotids!

One particular day, the resident had to be gone. Because it really takes two anesthesiologists to start a cardiac case (and I didn't and still don't count), there were two attendings there that day. They were both women in their 40's, laid back, good natured, and very skilled at what they did. With such a high attending-to-med-student ratio, I was feeling just a shade nervous but still happy to be there.

With the usually flurry of activity, the patient was brought into the room, moved to the operating table, and hooked up to monitors. One must understand that in the OR, time is money. It's often cheaper in the long run to use a more expensive drug if it means a faster turnover time in the OR, or if it gets the patient out of the PACU (peri-anesthesia care unit) faster and without respiratory or cardiovascular compromise. And with that mindset, I swiftly aided, attaching the blood pressure cuff around the patient's arm and locking the pulse-oximeter probe onto his index finger.

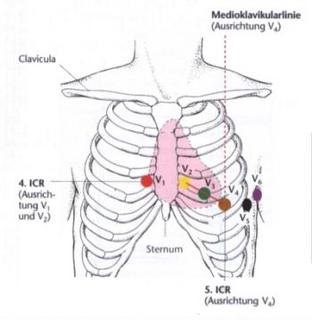

You may wonder where our theme of EKG's comes in. Right about here. In basic OR cases, all that's needed to monitor a patient's heart is a three-lead EKG. One lead on the right shoulder (white), one lead on the left shoulder (black), and one on the patient's left flank (red). But in these cardiac cases, we need a couple more leads checking the heart from front to back, called "precordial leads," labeled V1-V6 in the diagram below.

I attached the three basic leads, and there I was left with an orange and brown lead. "Which one went where???" I thought to myself. I felt like people were waiting on me, as both attendings had finished their work and were ready to induce anesthesia as soon as I got the leads hooked up. I seemed to remember orange went on the right of the sternum, so I hurredly placed a sticker there and clipped the lead onto the metal snap-like piece protruding from the center of the sticker. "That leaves me with brown," quickly moving the lead toward the spot labeled V4 above.

Only there wasn't a sticker there already. What the metal pincher was headed for was not a carefully positioned sticker, but the poor patient's nipple. I suppose it technically would have still worked. But I am forever thankful that I stopped one centimeter away when a little voice in my head said, "Wait, something's not right!" Both attendings had seen my near-blunder, and I'm sure the story will be told and re-told about that lanky med student who nearly pinched the EKG lead onto a man's nipple. But I didn't. And it makes for a good story. And maybe, because I've posted this, someone, somewhere down the line, will avoid the same mistake!

2 comments:

Wow--I thought this story was bound to provoke at least a few comments! Maybe my narrative is too long, notwithstanding its being punctuated with helpful pictures and diagrams.

Jonathan, I thoroughly enjoyed it, as well as your other posts. Thanks to David for passing along the address!

Laura

Post a Comment